Two Years Building with Generative AI in Government: What I've Learned

I joined DBT nearly five years ago, building internal products like a leavers service and an internal risk and assurance service. Two years ago, our Chief Data Officer moved me to a newly formed AI Enablement team to implement Redbox, a colleague-facing LLM product. Over the last two years we’ve built out from 12 test users to over 3000 - and I’ve learned that the hardest problems aren’t the ones I expected.

What We Built

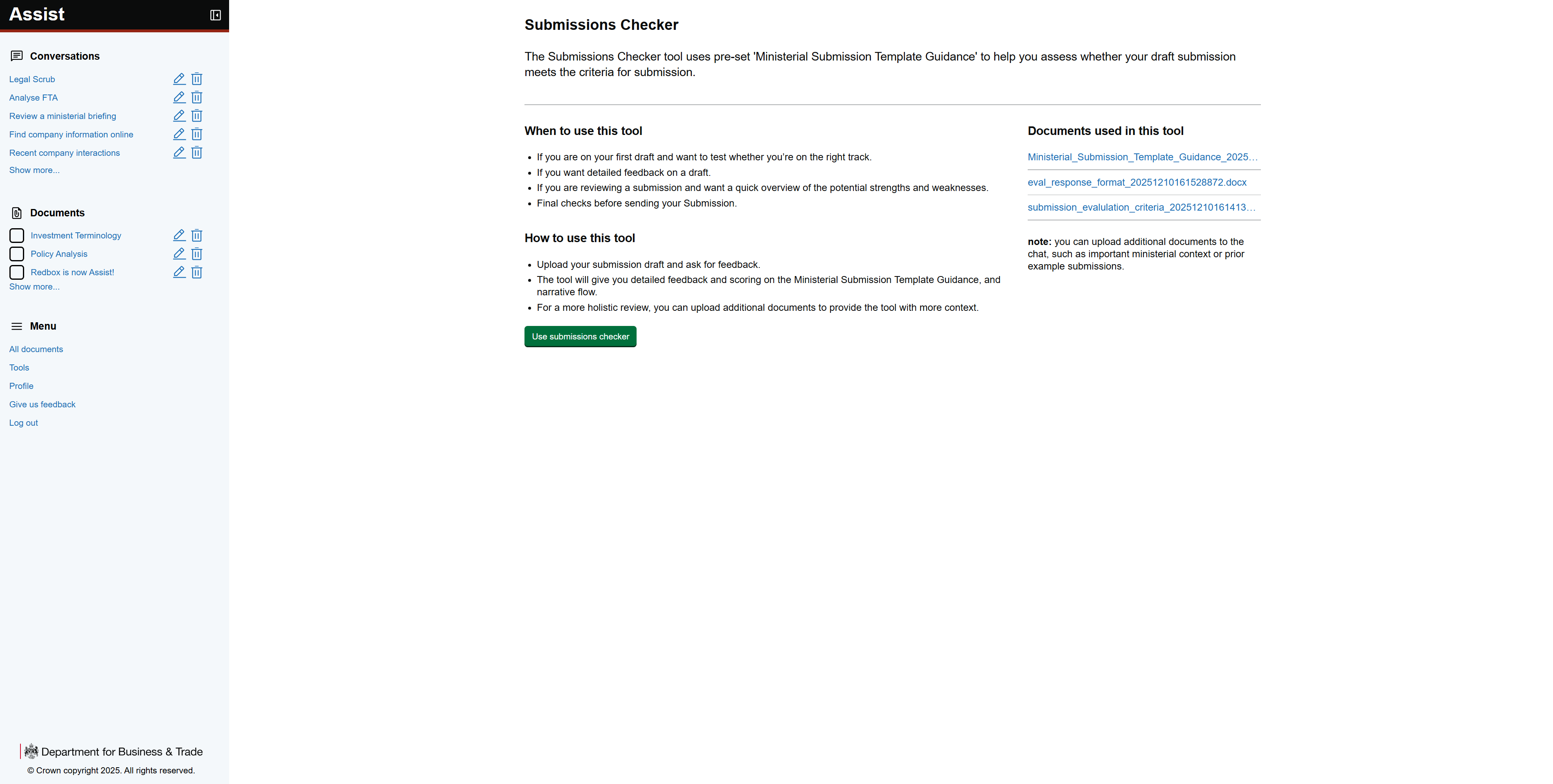

In mid 2024 we forked i.AI’s Redbox and built Redbox at DBT - a (now) fully agentic service for colleagues handling Official-Sensitive material. Our agentic approach is hand-rolled, and handles web search, GOV.UK and legislation.gov API lookups, serial and parallel tool calling, agent queuing, multi-model orchestration and MCP integrations. We’ve built tools like InvestLens, which pulls from integrated data sources to generate company intelligence briefings, and a Submissions Checker that provides automated feedback on draft ministerial submissions, with a Negotiation Planner in development.

This design doesn’t deviate much from the original i.AI design system/style, and users felt it felt ‘clunky’, not ‘modern’ - consumer grade product design expectation means that users will choose other products over yours, regardless of utility.

This design doesn’t deviate much from the original i.AI design system/style, and users felt it felt ‘clunky’, not ‘modern’ - consumer grade product design expectation means that users will choose other products over yours, regardless of utility.

i.AI sunsetted their version of Redbox in December last year. This wasn’t failure - it’s the natural lifecycle of pioneering tools, and the big bet the UK Government has taken on MSFT Copilot (more on this later) meant there was no perceived need for a product-team-led LLM service built and managed centrally. i.AI are still building out Consult and Extract (and many other tools) - products being tested across government, and the overall Gov landscape is tilting towards at least some level of centrally built, deployed and managed generative AI tooling.

At DBT we quickly moved beyond the base Redbox platform, iterating on specific use cases and keeping GDS Cost Per Transaction well within the ‘Very Good’ category. That required a product team who understood both the technology and the users. You can’t do agentic workflows out of the box - and you can’t bolt on source tracing and audit trails after the fact. In government, every output might need to be justified in a PQ, an FOI request, or a court. That shapes how you build from day one.

I’m not a data scientist, but I’ve built RAG systems, worked with embeddings and can code just enough to be dangerous so I understand enough about the underlying patterns to work with the team to make the right decisions early. This kind of work isn’t wholly driven by traditional software engineers - it’s largely driven by data scientists and ML Ops engineers. Being able to speak their language, understand the trade-offs, and make informed decisions builds trust. Demands are high, we need to move quickly, and you can’t afford to get stuck in decision-making loops.

The Design Problem

This is the part I haven’t read much about elsewhere.

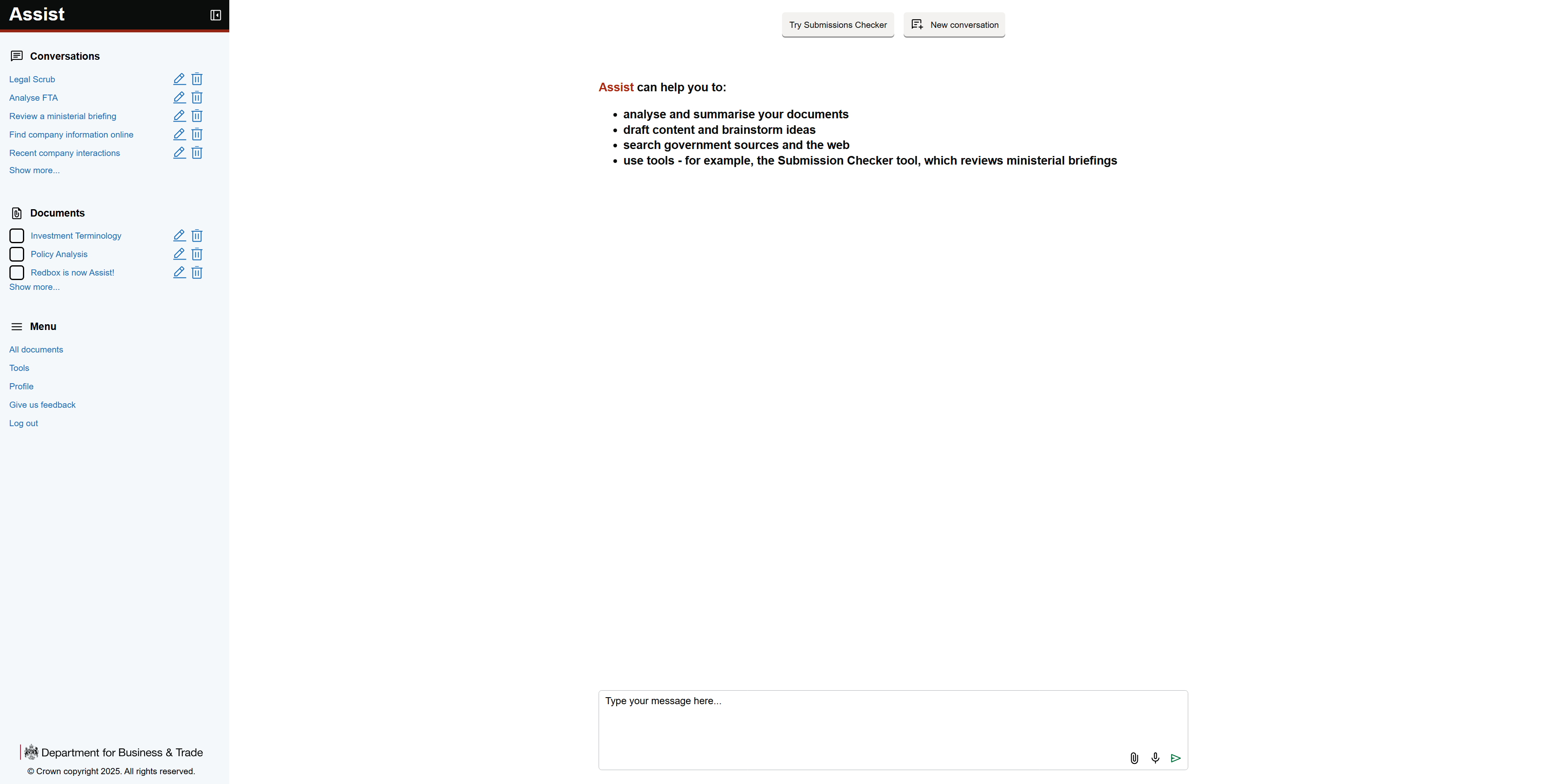

Civil servants use ChatGPT or Claude at home. They expect modern interfaces. But GDS components weren’t built for conversational interfaces. It’s a lot like the BYODTW (bring your own device to work) challenge which so many organisations had to face back in 2007 when the first iPhone launched. For Redbox’s recent relaunch as Assist — which Saisakul and I wrote about on the DBT blog today — we had to create new patterns focused on maximising available space for dialogue, while preserving the trust signals that matter: the crown logo, departmental branding; the visual language of gov.uk products and services. This is a good thing, it means we can play back our design decisions and hopefully add to the shared knowledge which is the GDS, but it’s not easy - lots of internal debate, and you need to be able to defend choices like this at Service Assessment.

Redbox newly framed as ‘Assist’, with the header and footer abstracted to inhabit only the sidepanel, giving lots of needed space for work to happen in the conversation window.

Redbox newly framed as ‘Assist’, with the header and footer abstracted to inhabit only the sidepanel, giving lots of needed space for work to happen in the conversation window.

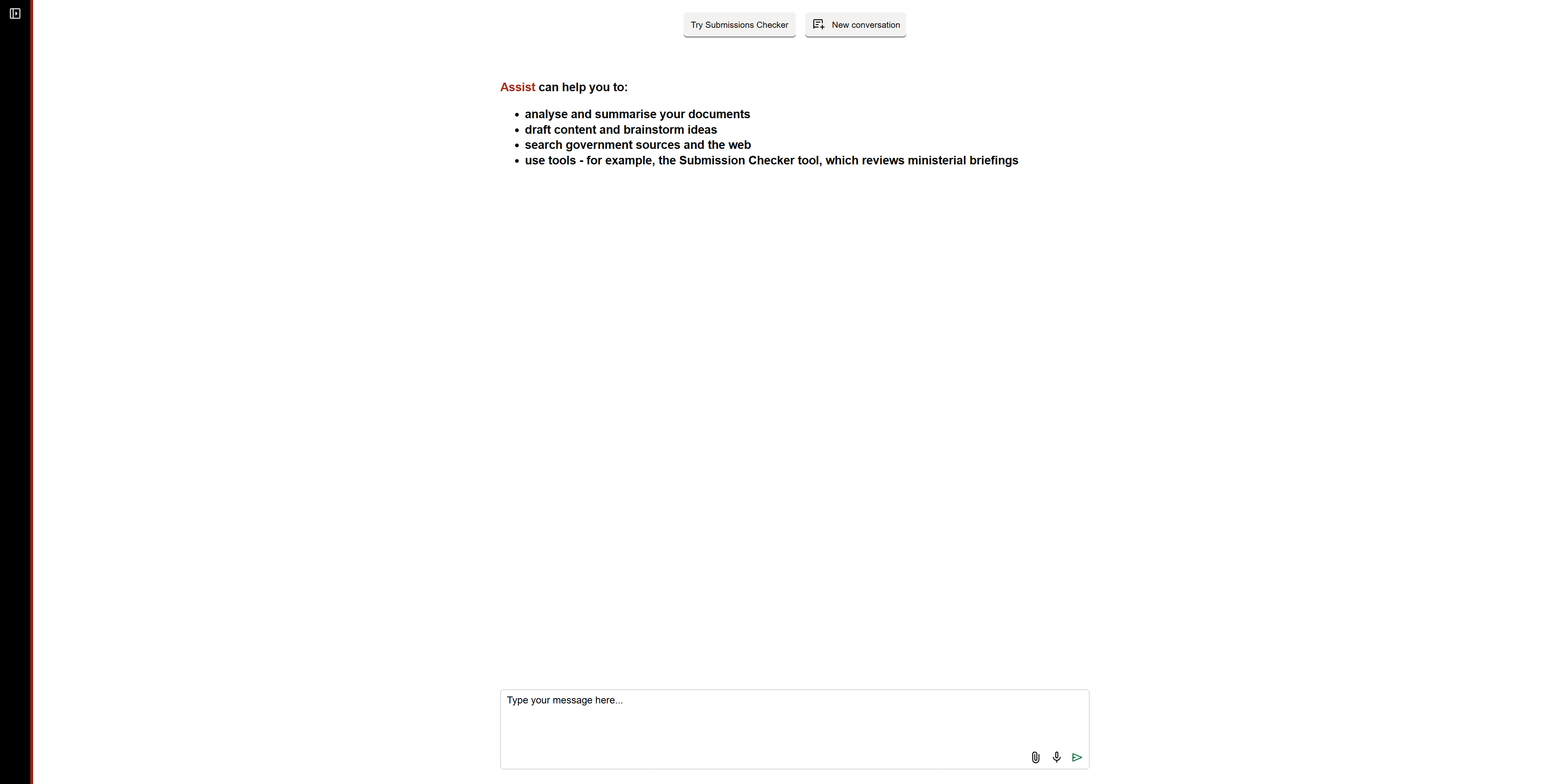

With the sidepanel collapsed, even colleagues on tiny screens have ample room to work, removing the feeling of friction and cramped-ness which defined the original design for many users.

With the sidepanel collapsed, even colleagues on tiny screens have ample room to work, removing the feeling of friction and cramped-ness which defined the original design for many users.

These design decisions are not superficial, they’re why colleagues trust the service with Official-Sensitive documents, and critically, reduces friction in a new type of interface. Trust goes deeper than branding - civil servants need to stake their professional credibility on the tool’s output. If it goes into a ministerial submission, it’s their name on it (human-in-the-loop by design of course). One Policy Advisor described the Submissions Checker as an “independent pair of eyes” that helped “avoid documents being returned for corrections” — that’s the kind of trust you have to earn through design, not just functionality. Internal colleague-facing LLM product development is not really that different from citizen-facing; trust is critical when you’re asking people to change how they work or access information.

The Microsoft Copilot Question

The UK government signed a five-year agreement with Microsoft in late 2024. In 2024/25, departments spent £1.9 billion on Microsoft licenses. HMRC alone has 32,000 Copilot licenses scaling to 50,000.

The cross-government Copilot experiment was instructive: 20,000 civil servants, 26 minutes saved daily. But the official report, published September 2025, found “no evidence time savings led to improved productivity.” Policy teams struggled with nuanced, context-heavy work. At DBT, we ran our own evaluation - 72% satisfaction, clear wins on drafting and summarising, but Policy and Legal roles found it less useful, and 22% of users identified hallucinations. That matters: government workers in high-impact roles carry huge responsibility for accuracy and being able to justify their decisions. Knowledge workers in complicated roles need comprehensiveness, not surface detail. You can’t cite “Copilot said so” in a ministerial submission. Rigorous M&E matters when you’re deciding where to invest.

This isn’t a criticism of Copilot - it’s about the gap between generic products and real user needs. If you need to analyse a 1000-page document and through the corrections made produce a similar-length final version with reliable source tracing, Copilot can’t do that. Building an agent in Copilot Studio as a non-developer won’t get you there either. These are complex data science problems. You need product teams who can bridge that gap. Maybe only 10 people in one team need this capability - but if it saves 30 days of work and contributes to a successful free trade agreement, the ROI is enormous.

The Landscape

The pattern across government is consistent so far: summarisation and search first, generation carefully. Document processing looks easy/cheap but doing it well is hard.

The Roadmap for Modern Digital Government (January 2026), makes AI one of six pillars - alongside joining up services, digital infrastructure, leadership and talent, funding reform, and transparency. It’s the clearest signal yet that this isn’t optional experimentation. The PM’s AI Exemplars Programme is testing real-world use cases across government, with GDS creating central guidance for responsible AI development and procurement.

The largest operational departments are building infrastructure. HMRC established a GenAI Landing Zone in mid-2025 and trained over 7,000 staff. DWP reversed its LLM prohibition in early 2025 and committed £12 million to capability building - they’re recruiting senior GenAI leadership now. These are serious investments in foundations.

Where citizen-facing AI is emerging, it’s measured. GDS launched GOV.UK Chat in private beta in late 2024, and recently Anthropic announced a partnership to drive this even more. DVLA’s chatbot handles 300,000 customer queries monthly. DBT launched its first public-facing AI on business.gov.uk in August 2025 - a funding summariser that helps businesses discover tailored grants and loans through structured queries rather than browsing scattered pages.

The contentious work is in consequential decisions. Home Office’s asylum tools show real efficiency gains - 37 minutes saved per case on policy search - but they’ve attracted scrutiny. That’s appropriate. The roadmap emphasises that accountability must be built in, with frontline public servants overseeing individual decisions. AI in high-stakes contexts needs rigorous governance, and we should expect public debate about where and how it’s used.

Where It Goes From Here

The AI Opportunities Action Plan set the direction in January 2025: AI leads for each government mission, regulators required to publish annually on how they’ve enabled AI-driven growth. The Roadmap for Modern Digital Government goes further - it’s a comprehensive strategy across six pillars, with AI embedded throughout rather than siloed.

The technical direction is clear: multi-agent orchestration, cross-department reuse over bespoke builds (there are many hills to climb to make this happen), and services that actually join up. GOV.UK One Login, GOV.UK Wallet, a unified app experience - the infrastructure for citizen-facing AI is being laid. And now there’s CustomerFirst - a new GDS/DSIT unit led by Tristan Thomas (ex-Monzo) with Octopus Energy’s Greg Jackson as co-chair, focused on radical improvements to high-impact services. They’re operating with startup pace and pulling in private sector expertise alongside civil servants. When the roadmap talks about making services “simpler, faster and more personal,” CustomerFirst looks to me like a delivery vehicle.

The talent question is a binding constraint. The roadmap acknowledges it directly: only 6% of central government staff work in digital and data roles (policy is in place to increase this to 10% by 2030). Of £26 billion invested in digital and data in 2023, substantial portions went to external consultants rather than permanent staff. They’re introducing competitive pay frameworks to change that - but building internal capability takes years. In the meantime, government needs people who’ve shipped production AI, not just piloted it. Who’ve navigated the governance, built the interfaces, measured the outcomes. That experience exists, but it’s scarce. And when it comes to data science talent, we’re competing with people like Meta who are quite literally throwing billion dollar contracts at talented machine learning folk.

We’ve Only Just Begun

Navigating government services remains… hard. Finding the right information, understanding eligibility, completing applications. The roadmap’s vision - joined-up services, proactive support, things that actually work first time - is IMO the right approach to really making government services easy to access, use, and get the answers you need, faster.

The constraints are real - governance, stochastic outputs, procurement, legacy systems, a lack of data-readiness, public accountability. But those constraints force you to build things that actually work, for users who actually need them, with outcomes you can defend. That’s what makes this work worth doing.